We apply a new generation of label-free single-molecule methods to go beyond the current sensitivity and speed limits of single-molecule methods.Our overarching ambition is to create the tools needed to understand and control biological membranes. To achieve this, my group develops new single-molecule methods for optical imaging and creates new forms of artificial membranes. We then actively demonstrate the power of combining these complementary tools by addressing specific outstanding questions facing membrane biology.

Engineering artificial mimics of the cell membrane

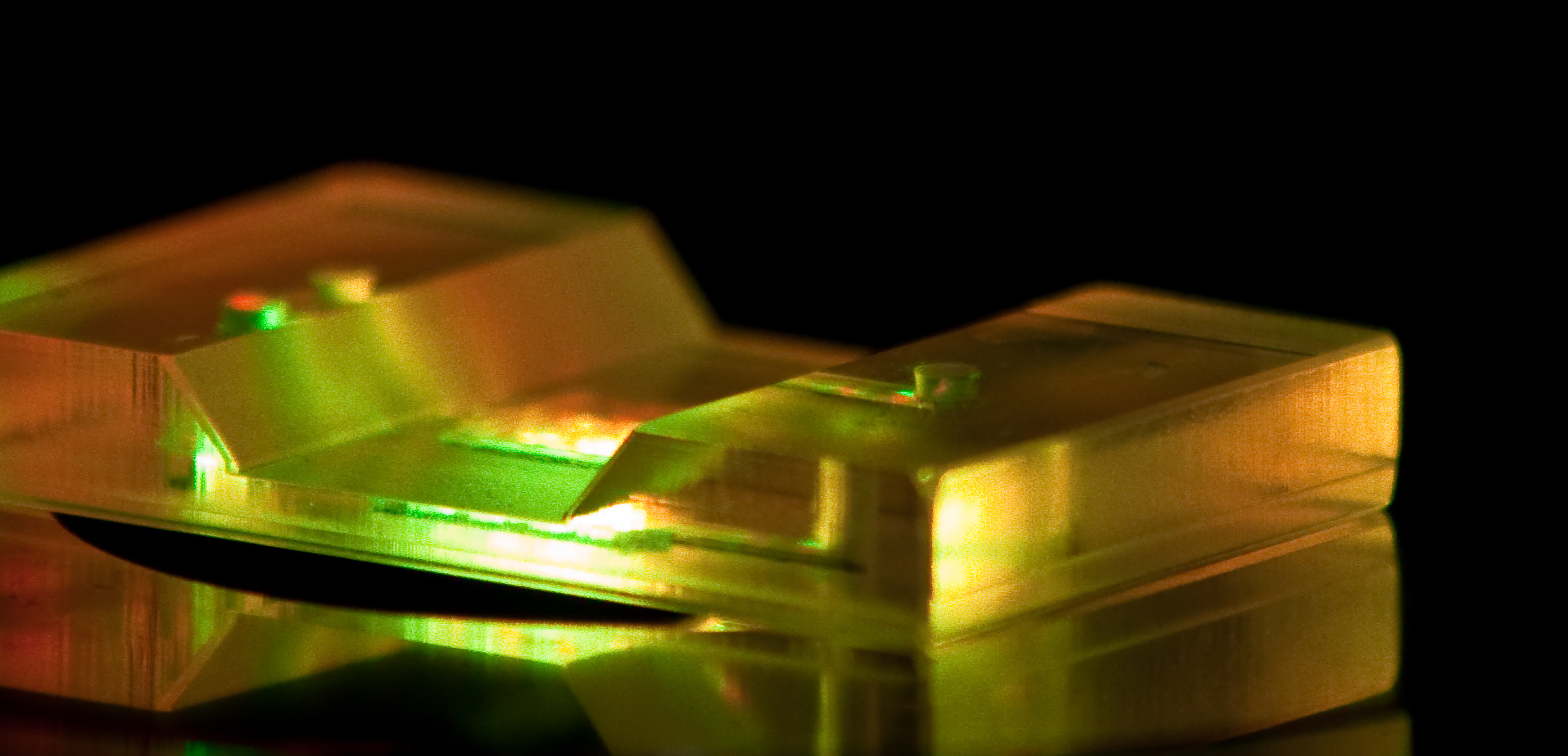

Using microfabrication and 3D-printing we build mimics of cell membranes from their component parts. This helps us understand precisely how these components work together. It also lets us build artificial protocells with new emergent properties. Using microfabrication and 3D-printing we develop new artificial lipid bilayers that give us control over membrane properties.

Overall, these new tools have enabled us to explore the role of many fundamental physical drivers of membrane function - including asymmetry, curvature, corralling, and crowding. Key to this has been to develop ways to manipulate membranes that are compatible with our new imaging tools - permitting single-molecule resolution of these processes.

Current work targets two specific areas for future development: (1) Artificial cell division and (2) artificial membrane synapses.

New single-molecule tools

Single-molecule microscopy has the power to reveal the dynamic heterogeneity that governs complex biological processes. We have pioneered methods for combining single-molecule fluorescence microscopy with single-channel recording to pursue a classic ‘structure-function’ approach at the level of individual ion channels.

Now we seek to step beyond the spatial and temporal limits of current single-molecule fluorescnce methods, exploit label-free imaging of membrane proteins and lipids.

New membrane biology

We are interested in precisely how large macromolecular protein complexes can assemble in a membrane. What drives this assembly, and how can we control it? Developing these new methods is worthless if those methods are not then widely adopted. Showing the potential of our new methods has been a major factor in our efforts - focusing on a few decisive examples where our impact can be more clearly demonstrated.

Pore-forming proteins have been a common theme, where we have examined the assembly dynamics of small and large beta-barrel pore-formers and applied these proteins to nanopore sensing. We have also brought our methods to bear on GPCR function, revealing a dynamic dimerization process essential to the neurotensin receptor NTR1, and to the complex orchestration of protein components required for twin-arginine directed transport of folded proteins from bacteria.